There are four versions of any idea:

The idea in your head

The words you use to express it

The words the other person actually hears

The idea they walk away with

Most communication breaks in the gaps between these.

We tend to obsess over version one: “I know what I meant.”

But outcomes are driven by version four.

If you care about communicating well, your job isn’t to defend the idea in your head.

Your job is to translate it so the idea they derive matches your intent.

Where communication breaks

This translation fails in a few repeatable ways.

1) The words are lazy

You use vague or overloaded language. The listener has to guess what you meant, and they fill in the gaps with their own context.

This is what happens when we rely on buzzwords, abstractions, or “industry language” instead of saying what we actually mean.

When this happens, the failure isn’t on the listener. It’s on the speaker.

2) Attention drops

Your words are fine, but they don’t fully land.

They skim. They’re tired. They’re multitasking. They’re thinking about something else.

Or they were reading Slack during your Zoom call.

3) The words land, but the meaning changes

They heard you correctly, but mapped it to a different idea.

“I thought you meant X.”

“No, I meant Y.”

Example: you said you’d “score email addresses.” They thought you meant a 10-point propensity model. You meant a simple valid/invalid check.

4) They understood you and disagree or don’t care

This isn’t miscommunication.

It’s a real difference in beliefs, priorities, or incentives.

That matters, because the fix isn’t clarity. The fix is alignment, repositioning, or choosing a different audience.

If you don’t know where the breakdown happened, the experience degrades fast:

• Attention problem → you send more words, and they skim harder

• Interpretation problem → you repeat yourself, and they feel talked at

• Alignment problem → you keep explaining, and they feel pressured

Different failure. Different fix.

Why this matters in GTM

Go-to-market is communication with constraints.

You’re taking an idea and trying to move it through other people’s heads at scale:

• what the product does

• why it matters

• why now

• why you

• what to do next

GTM isn’t separate from communication.

It’s the business function where communication either works - or you don’t get paid.

“Good copy” isn’t the goal.

The goal is knowing what broke:

• Was the idea fuzzy internally?

• Were the words too abstract?

• Did it get seen but not processed?

• Did it get processed but misinterpreted?

• Or did it land clean and they simply disagree?

Buyer timing makes this harder

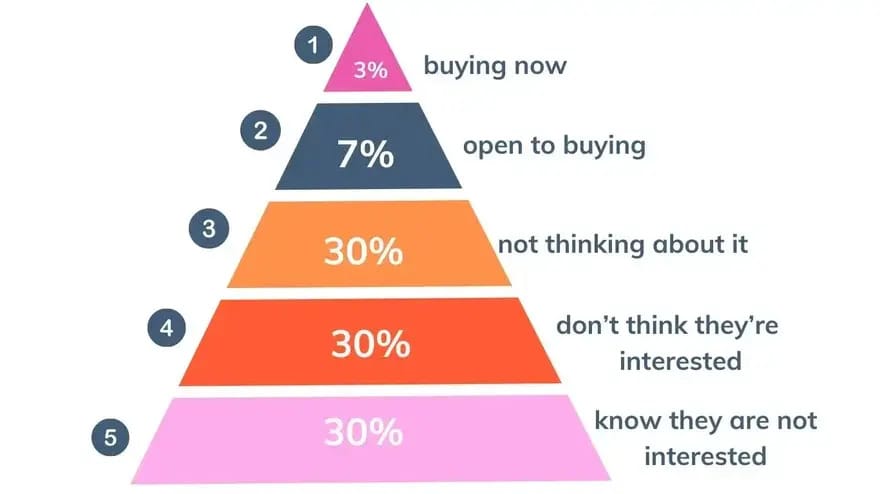

Chet Holmes described buyer readiness roughly like this:

• 3% are ready now

• 7% are open

• 30% aren’t thinking about it

• 30% think they’re not interested

• 30% know they’re not interested

The exact numbers don’t matter. The shape does.

Most people are not “ready” when you speak.

If you rotate that pyramid sideways, it becomes a timeline.

People move through readiness over time as context, priorities, and incentives change.

Everyone becomes a buyer eventually.

Why mediocre GTM feels hyper-competitive

Mediocre GTM mainly works on people who are already in motion.

It resonates with the 3% and 7% because those buyers are actively looking.

That’s why it feels crowded.

Everyone is fighting over the smallest slice of the market, at the loudest moment, using similar language and similar claims.

You can win there.

But you’re playing in the noisiest arena with the smallest addressable moment.

Great GTM activates the next 30%

Great GTM does something harder.

It lands with people who were not thinking about the problem yet.

That next 30% is a much bigger opportunity - but only if your communication is excellent.

You don’t activate that group with “we help you do X faster.”

You activate them by creating a new idea in their head:

• naming a problem they didn’t have language for

• reframing what felt normal as expensive

• exposing a tradeoff they’ve been living with

• making the cost of staying the same feel obvious

When someone isn’t already looking, clarity and truth are the only things that work.

If you can do that, you face less competition and operate earlier in the buying cycle.

The job

Most GTM teams don’t have a copy problem.

They have a translation and diagnosis problem.

You start with an idea. You ship words into the market. You get results back.

When results don’t match intent, the instinct is to change tactics:

• new subject lines

• new channels

• new personas

• more volume

• better timing

But without knowing where the relay broke, you iterate blind.

Strong GTM teams can look at performance and say:

• the idea wasn’t sharp enough

• the language was abstract

• it didn’t earn attention

• it got misinterpreted

• or it landed clean and the premise was wrong

Different failure. Different fix.

In GTM, the goal isn’t “say it.”

It’s to make the right idea show up in someone else’s head; reliably, clearly, and at scale.